In late 2018, as both collectible fine wine and art markets were scaling new heights, two auctions in New York made headlines globally.

The first, a wine sale at Sothebys, smashed the world record twice in one night for the most expensive bottle of wine every sold – with two bottles of 1945 Romanee Conti fetching $496,000 and $558,000 respectively.

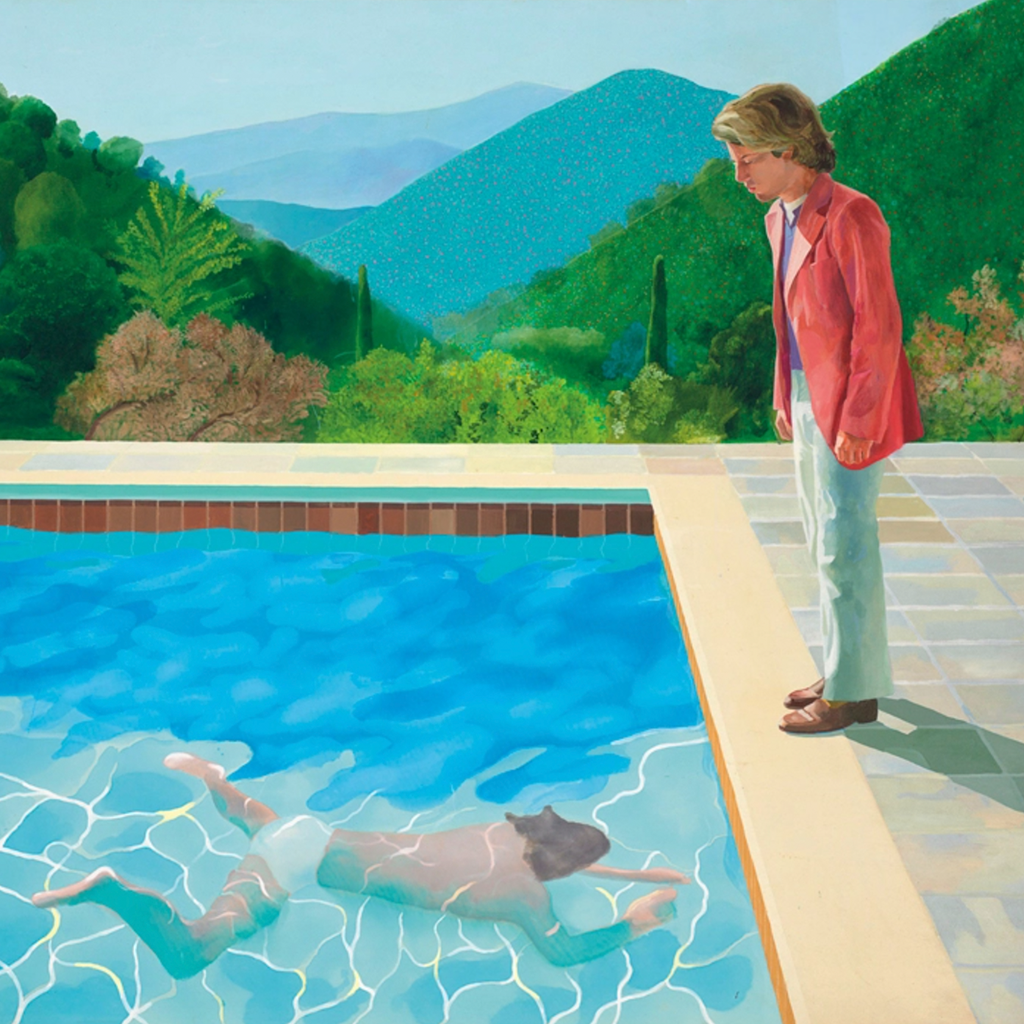

A month later, an art sale at Christies also broke new ground, with David Hockney’s “Portrait of an Artist” selling for a record $90 million.

Apart from their eye-watering prices, the results were driven by the same underlying factors. Both involved iconic and ultra rare collectibles.

At a time when interest in collectibles is soaring, one might be tempted to extrapolate from these results that fine wine and art play by similar rules. Master one, and it should be possible to replicate this with the other – correct?

Erm, not quite. This may be true at the very top end – rarity and genius are simple to understand. But the differences come sharply into focus as one moves down the value chain.

What follows is a brief look at how fine wine and art stack up against each other, told through the medium of famous paintings:

Leonardo da Vinci – The Mona Lisa

For centuries, the Mona Lisa’s enigmatic smile has been saying to people: “I know something that you don’t.”

Therein lies the rub of art collecting. No matter how long you spend wandering around galleries and dabbling in the market, the most critical factors influencing prices will remain shrouded in mystery for most.

A wine’s quality is subjective, but art takes that to another level. Great art, we are told, is not defined by something as trivial as whether you enjoy looking at it or not.

That’s because the people and institutions who control the art market, namely galleries and auction houses, exert enormous influence over who makes it and who doesn’t.

When a top gallery endorses an artist, demand and prices rapidly follow. They are the puppet masters of taste and value.

In this recent article, Quartz magazine stated that “galleries manipulate prices to an extent that would be illegal in most industries. Someone with a financial interest controlling the market is worrisome. In any market, price manipulation causes distortions, shortages, and inefficiency.”

If this system existed with wine, it would be like a top critic partnering with a chateau and saying “I’ll give you rave reviews and high ratings from now on, and in return I get a cut from every case you sell.”

Fortunately, wine critics don’t wield that sort of power in any event. While their tasting notes certainly move prices, taste is ultimately determined by the market. Even a high rating often won’t save a wine that collectors don’t like, and critics who don’t pay attention to this may quickly become irrelevant.

The wine market, meanwhile, has become increasingly transparent over recent years. Collectors can now choose between multiple trading platforms displaying bids on thousands of top wines, and commissions as low as 2.5%.

This isn’t to say that an amateur can’t be successful in buying art. It’s just harder, and the risks are higher, when you’re playing against the house.

Small collectors should go in expecting to have the odds stacked against them. Not only will the best pieces get pre-allocated to more serious collectors, but you will likely pay full prices coming in, and full fees going out.

Andy Warhol – “Dollar sign”:

The fact that something is collectible usually means that it’s special in some way and, ipso facto, doesn’t come cheap. That is especially the case with investable art.

To determine if a fine wine is investable, one must look first at qualities such as its brand strength, reputation with critics and collectors, and other factors such as vintage and relative value considerations.

The lowest entry point for a 12-bottle case of investment quality bottles is probably close to €1,000. Yes, you can go lower but the pool of potential buyers is limited, so your chances of making a positive return are slim. The greatest liquidity and potential for returns generally come at higher price points, with a sweet spot somewhere in the range of €2,000 – €10,000 a case.

On the surface, art plays by similar rules. For brand and history, one must look at an artist’s pedigree. I.E. where they went to art school, which galleries have exhibited their work, and how many of these were joint exhibitions vs more prestigious solo shows. In turn, track record is determined by an artist’s auction history: how many pieces have sold at auction, over what period of time, and how have prices evolved over time?

The biggest difference between collectible fine wine and art is the price of entry. For art, unlike wine, a good rule of thumb is that spending more – even into the millions – usually means lower risk and higher returns. This can be counterintuitive for newcomers, whose instinct may be to start off small and test the waters – only to find themselves with pieces that struggle to retain their value, much less increase.

There are always exceptions, of course, and it’s fun to read about someone who bought a piece for €10,000 only to sell it a few years later for €1 million. But these are unicorns. You are much more likely to read about $1 million paintings that soared to $10 million.

One reason for this disparity is volume. While some investment quality wines are produced in tiny quantities of 100 cases or even less, that is the exception. The Bordeaux estate Chateau Lafite Rothschild, for example, makes around 16,000 cases or almost 200,000 bottles a year. By contrast, even the most prolific artists are rarely able to turn out more than a dozen pieces a year, and each is unique.

The result is an imbalance between supply and demand that only increases the higher you go. Artists also need to survive, so selling paintings for €1,000, or even €5,000, won’t pay the rent for long after gallery commissions.

Hokusai – The Great Wave:

Okay, the art-work analogy here is a bit of a stretch, but anyone buying collectibles needs to think about liquidity.

One of the main advantages of wine is the ability to buy and sell it in multiple ways – through wine merchants, at auction or on trading platforms.

This enables amateur wine collectors to experiment, take risks, and learn along the way, while having the fall-back of knowing that they can always sell their mistakes. It won’t always be quick, but as long as you have reasonable price expectations, a buyer will usually come along eventually.

Art, on the other hand, is difficult to value and even harder to sell. There are literally millions of artists in the world, all producing new works on a steady basis. But unless they have the right credentials and track records, there is unlikely to be much of a secondary market for their works. That’s not to say that such works are entirely unsaleable, but it isn’t quick, easy or cheap.

Smaller collectors should expect to pay full fees to auction house of 25% or more. This is in contrast to the super wealthy with more established collections, who routinely have their fees cut or waived, and are even offered guaranteed prices at auction.

If you ask an art collector, and they’re being honest, most will tell you to do one of two things:

1) Buy what you love, preferably without spending too much, and write off the investment,

or

2) Spend a lot, on a piece from a recognised and established artist. You’re unlikely to get their best pieces, as these will already be gone, but get something you like, if not love. Then at least you’ll have something nice on your wall, and a chance of making money along the way.

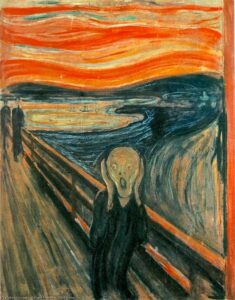

Edvard Munch – The Scream:

One of the perceived attractions of art is the potential to make a huge windfall by discovering the next hot thing.

What you may not hear about are the hot new things who soared, only for sentiment to reverse and prices to hurtle just as quickly back to Earth. Anyone left holding one of these pieces is likely to feel like the protagonist of the iconic painting by Edvard Munch.

To be fair, fine wine has had its share of sharp reversals – most notably in 2011. This was when speculative buying of top Bordeaux, reportedly fuelled by gift giving to politicians in China, dried up overnight due to an anti-corruption drive in the country.

However, the highs have rarely been as high, nor have the reversals been as dramatic, as those seen in the art world.

It’s important to point out here, in case it wasn’t obvious, that many people don’t just buy wine or art to make money. For many, a great bottle or painting is something that can inspire and bring joy, and this is not quantifiable with something as crass as money. There are even comparisons to be drawn between the two.

As legendary Burgundian winemaker Count Louis-Michel Liger-Belair noted in a recent article: “Wine is the ultimate piece of art because when you open the bottle, there is no more value. When you drink it, you destroy it.”

Even so, if asked, most people like to believe that their collectible of choice has inherent value, and perhaps has even appreciated, should their tastes or circumstances change.

This is where fine wine comes into its own – as arguably the most democratic and transparent of all collectibles.

On a personal note, when I was starting out in wine back in the late 1990s, I paid the princely amount of just over €1,000 at auction for a case of 1990 Chateau Palmer from the cellars of Earl Spencer, Princess Diana’s brother. The wine was glorious, of course, but I was also struck by the proximity to history that it provided me. By contrast, I couldn’t have imagined myself affording one of the famous paintings on the Earl’s walls.

This is the magic of collectible fine wine. Its ability to combine artistry with agriculture, past with present, and to bring people of all stations closer together – not separate them further.

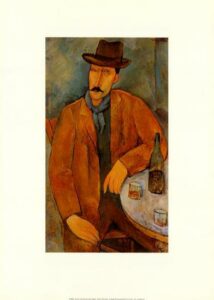

On that note, and at the risk of offending art lovers everywhere, I will leave you with a fitting portrait from Modigliani – “Man with a Wine Glass”- who was known to sell his paintings for jugs of wine from the local bars in Montparnasse.

If you would like to speak with a 1275 advisor or get a copy of our brochure, please click here: https://www.1275collections.com/contact/